Should We Continue Saving the Fur Seals

Each morning, before the sun peeps over the Cape Fold Mountains, Brett Glasby begins his patrol of Cape Town's Waterfront jetties. He carries a long pole with a hooked knife at the tip and he's hunting for plastic. Not just any plastic, but jetsam from the fishing industry that slips noose-like around the necks and bodies of seals. Sadly, there's no shortage of it.

Seals don't enjoy prodding by humans, but after many years of practice, Brett is skilled at hooking and slicing through often cruelly tight netting, box binding, fishing line, tuna suspension loops and rope. When it's so tight it has sliced into skin and flesh, he uses a large net with an endpiece that effectively muzzles the seal while he removes the entanglement.

We set off from the Two Oceans Aquarium, past the dry dock, the painted cows and the bronze statues of Mandela and Tutu, De Klerk and Sobukwe – Brett striding with his long pole.

He surveys the jetties between gently rocking tourist ferries and a looming ship with a bulbous radar nose at water level. Young seals are playing king-of-the-castle on the bulb, claiming the perch then being knocked off to much happy barking. Others are herding shoals of small fish against the jetty and gulping them down in a breakfast feeding frenzy.

Fur seals really are superfurry insulated. They have two thick layers – a soft inner fur and a waterproof outer layer. Below that is tough skin and a layer of blubber that keeps them warm in the freezing water in which they like to fish and play.

Sadly, in the past, this has made them the target for seal fur coats, which caused their numbers to crash. Fortunately, the practice was banned in South Africa, but clubbing baby seals still takes place annually in Namibia – cruelty for fashion under the guise of culling.

Further along the quay, some seals have gathered on a jetty at the stern of a massively ego-amped superyacht. "They shouldn't be here," Brett tut-tuts. "We try to train them to haul out on the platform near the aquarium."

He climbs down and shoos them off. A straggler dares him for a few moments before conceding, slipping into the water like a sleek torpedo with an annoyed "arf".

We drop down on to jetties lined with expensive luxury motor yachts. Backed up as they all are, their transoms are perfect seal platforms, giving them access to decks and, if the doors are left open, lounges.

"These owners hated seals and wanted them shot," said Brett, "but we educated them to use little portable picket fences to stop them getting onto the transoms. And we patrol their jetties and sluice down any poo. So now we have a truce."

There are about 1,7 million fur seals along South Africa's coastline, so they're not at risk. As hunters, they're very efficient (while being food for sharks, especially great whites). A study of their diet found it contained an array of sea creatures, including anchovy, horse mackerel, pilchard, round herring, lanternfish, lightfish, goby, chub mackerel, snoek, Cape hake, macrourid, kingklip, Agulhas sole, jacopever and chokka squid.

To stay warm and healthy in the icy Cape waters, a 72kg seal eats about 3,8kg of food a day, or 1,4 tonnes a year. Taking that as an average and multiplying it by the estimated seal population, this equals 2,4 million tons of food a year. Local fishermen aren't nearly that successful and have been known to blame seals for poor catches.

About 250 seals live in Cape Town's V&A Waterfront. More and more, however, are getting snagged by plastic. Since the end of December 2021, the aquarium team has disentangled nearly 100, about twice what they usually help in a year. Brett's not sure why the increase. More plastic? More seals? Maybe the Cape harbour area is just more comfortable or has more accessible fish. In the Waterfront, however, they get disentangled, whereas elsewhere they die.

"If you walk along Strandfontein beach after a southeaster," he says, "you're guaranteed to find a seal carcass tangled in ghost net or fishing gear."

In the South Atlantic, conditions appear to be changing, with more southern seals – elephant seals and even leopard seals – pitching up where they never used to be. Are climate change and warming oceans depleting food supplies? Hard to say, but it's possible.

Seal entanglements come mainly from bait box bands used by the fishing industry. Instead of cutting the plastic strapping, fishermen slide it off the boxes. If it's dropped in a bin on board, a strong wind or heavy sea can flip the bin over the side. Fishing line is also an issue – mainly tuna loops made of nylon cord used to hang tuna by their tails. Then there's abandoned netting.

"We've even had laptop bags," said Brett, "but most of it comes from the fishing industry. There's just a lot of thoughtlessness."

So Brett's on a mission to promote thoughtfulness. The solutions are not difficult, he explains. Fishermen could cut the box bands, for a start. The manufacturer could put a perforation in the tape every 20cm or 30cm so it pops when extra pressure is applied. They could use glue to bind them that dissolves in seawater.

It's also about educating the next generation. Brett takes kids around the Waterfront, getting them excited about wildlife. Apart from many birds and seals, there are sunfish and even, occasionally, a humpback whale.

"Nature's with us all the time," he explains as we circle back towards the Two Oceans Aquarium. "We've stolen wild environments and created our own. Wild animals are in our space – spiders, birds, bees, bats, chameleons – they're wild creatures we take for granted. But once we start noticing them, a whole new world opens up.

"I'm mainly the land-based guy," he explains. Divers like Claire Taylor and others in her team hook up through the slats of the seal platforms and get plastic off from below. Often seals are sleeping and don't even notice.

"We have employees who came to the aquarium as school kids, got excited, studied environmental issues as undergrads, did their postgrad research here and are still here, passing on their excitement and enthusiasm."

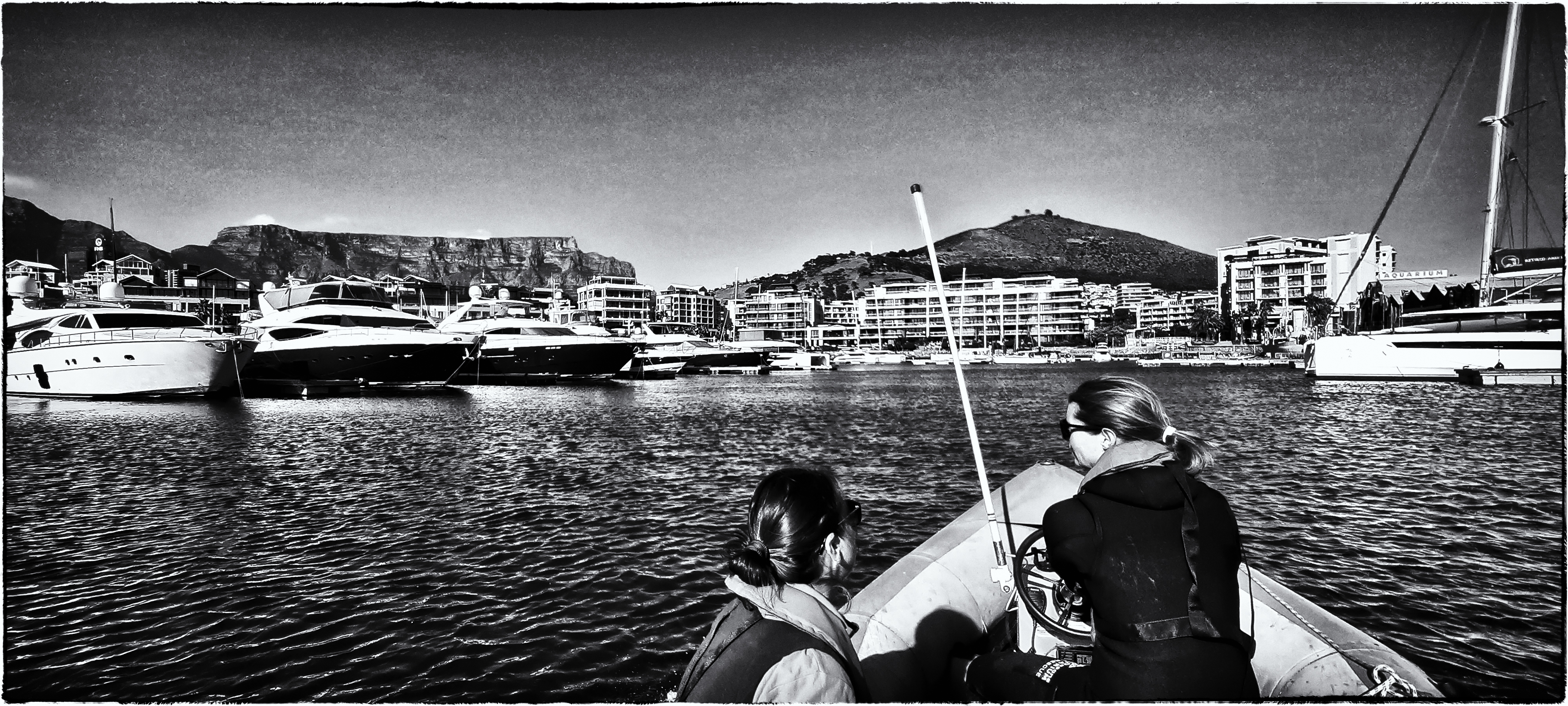

Claire is one of those. She started as a volunteer at the aquarium 22 years ago and now heads dry exhibits and marine welfare. But importantly, she's a class 4 research and commercial diver. What she likes best is getting into a wetsuit, firing up the rubber duck, sliding into the water and approaching seals from below with a cutting hook.

It's not something many divers would do. As she approaches an entangled seal from below the slatted deck, pee and poo can rain down on her upturned mask as she slowly raises the hook to snap off a box strap.

"I'm not much of a reader, I'm a doer," she tells me as we motor across the water on an inspection circuit. "I'm more of a field agent, happy to go pick up your otter poo and seal poo and give it to a researcher. A whisker here, anal jelly there. That's when I'm happiest.

"Seals are very playful animals with torpedo-shaped heads, so loops go over easily then stick as their body widens further back. And then, as the animal grows, it cuts through their breathing pipe or they die of infection from an open wound."

Claire docks the rubber duck with remarkable dexterity, ramping it up out of the water and into its cradle with a roar of the outboard. Then we head for coffee at Bootleggers overlooking the noisy seal deck.

"The best part of being the aquarium's marine welfare specialist is that I get to dive," she says, looking a bit like a seal herself in her black wetsuit. "I've been working with seals for 15 years and I'm never happier than when I'm on or in the water."

Recently she had a breakthrough. When she or Brett don't get to a seal in time, the band cuts deep and it takes an operation to repair the damage – that means immobilising the animal.

"We couldn't dart them because they'd head for water and drown. Then we came across a technique being done in British Columbia… a drug that doesn't knock them out completely, so they stay on the surface and we can get to them. It changed our methodology."

Later I find Brett checking bags of plastic straps, bits of netting and rope. "We record every freeing and send the information to the Department of Environment for research purposes. If only we could get the fishing industry to understand the damage their crews do through carelessness or thoughtlessness. It's all about education."

Then he stares across the dry dock at boats tugging at their moorings in a sudden dawn breeze. "I love the early mornings and the Waterfront," he says. "It's really cool, so peaceful…"

Somehow a group of barking seal pups on the deck below is part of his peace. If you listen right, it sounds like laughter. DM/OBP

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here .

![]()

Source: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-05-03-va-waterfronts-wildlife-heroes-saving-cape-fur-seals-one-plastic-noose-at-a-time/